(Hint: They’re Ancient) By: John Brownlee

In 1969, the New York Times asked Vladimir Nabokov, the famous Russian-American author of Lolita and Pale Fire, how he would rank himself amongst all living and dead literary greats, He slyly responded: “I often think there should exist a special typographical sign for a smile — some sort of concave mark, a supine round bracket, which I would now like to trace in reply to your question.”

Of course, almost 50 years later, there is. Type a colon followed by a “supine round bracket” into any phone or modern operating system, and it’ll spit out a smiley emoji — the exact same sly, supremely ambiguous and all-serving symbol that Nabokov imagined all those years ago. So did Nabokov “invent” the emoji, as publications like Lapham’s Quarterly now sometimes claim?

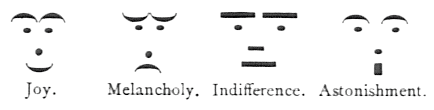

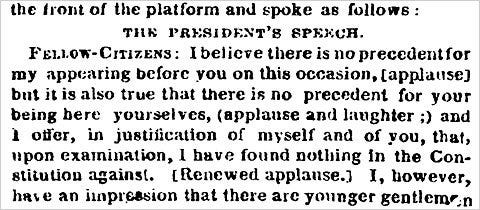

Well, if he did, Nabokov wasn’t the first. Writing in 1912, American author Ambrose Bierce proposed a character describing irony — he suggested — which should “be appended, with the full stop, to every jocular or ironical sentence.” Before that, in 1881, the U.S. satirical magazine Puck proposed four proto-emojis, which the editors called typographical art; made up of closely spaced hyphens, periods, and parentheses, they all resemble emoji that anyone can find on their phone, tablet, or laptop today. Even Abraham Lincoln is sometimes called the father of emoji, due to a transcription of one of his speeches from 1862, which features a winking smiley — ;) — after a note to wait for “applause and laughter.” And you can trace it back even further if you want to.

While interesting, in a way this is all navel-gazing. The truth is, emoji has no one “inventor.” There are, however, multiple people who came up with similar answers to the same problem: How to print images as efficiently as text while adding a little whimsy along the way.

What makes an emoji different than an emoticon, a sticker, a GIF, a drawing of that same thing? Emojis aren’t ad hoc; they’re characters, taken from a universal library of symbols. Curated by the Unicode Consortium, a nonprofit backed by Apple, Google, Facebook, Adobe, and other big tech companies, the idea behind emoji is that if you type in, say, a barfing face icon on your iPhone, it should display as a barfing face icon on any other modern device, regardless of what fonts are installed, whether it’s connected to the the internet, has the most up-to-date software, and so on. Most important, it should do so efficiently, using no more data for a single emoji than would be required to convey an alphanumeric character.

The technical groundwork for emoji was originally laid in 1999 by Japanese mobile phone company DoCoMo, which was trying to solve a very distinct problem. The network was about to launch i-mode, the very first mobile internet platform. On that team was a young engineer named Shigetaka Kurita. Because of the technical limitations of a mobile Internet platform running on pre-3G infrastructure, i-mode was to be text only, no images. But Kurita thought that was nuts.

“Even the weather forecast was displayed as ‘fine,’” Kurita explained in aninterview. “When I saw it, I found it difficult to understand. Japanese TV weather forecasts have always included pictures or symbols to describe the weather — for example, a picture of sun meant ‘sunny’… I’d rather see a picture of the sun, instead of a text saying ‘fine’.”

Kurita’s solution? For i-mode, DoCoMo’s engineers established a library of what we now call emoji — -a repository of 180 symbols inspired by manga, street signs, which DoCoMo built into every phone they sold. Now, when the network wanted to send an image to its users, it didn’t have to transfer the whole file, which might take up hundreds of kilobytes; it could just transfer a couple bytes of code and every phone would know what sticker to reference.

And that’s how emoji continue to work to this day. In fact, the Unicode Consortium’s official specifications for the emoji standard still include DoCoMo’s original 180 characters.

So is Kurita, as the Wall Street Journal claims, the real “father of the emoji”? Certainly, he has a good claim. But go further back, and you can find even more famous designers coming up with the same technical solution for slightly different versions of the same problem. And their emoji designs live on in the standard, too.

Johannes Gutenberg himself can claim to be the father of the emoji.

In 1990, Charles Bigelow, principal of the famous Bigelow and Holmes design studio, created the Wingdings font along with his wife, Kris Holmes. Originally three separate fonts called Lucida Icons, Lucida Arrows, and Lucida Stars, the Wingdings font was invented as a library of symbols that would elegantly complement Bigelow and Holmes’ other famous font, Lucida, without bloating document file sizes and download times with large, low-res image files. For his symbols, Bigelow drew inspiration from every era: “Pointing fingers and hands go back to medieval manuscripts,” he told Vox in 2015. “And, before that, to ancient Roman gestures; airplanes are 20th-century inventions; and keyboards, computers, computer mice, and printers, included in the Lucida Icons fonts, were part of office life in 1990 when we drew the images.” Wingdings hit the mainstream when Microsoft licensed the Lucida family, giving Windows users their first taste of proto-emoji goodness.

Twelve years before Lucida’s birth, in 1979, Bigelow’s own mentor, the legendary typographer Hermann Zapf, came up with his own emoji library, ITC Zapf Dingbats. Containing over a thousand designs for signs and symbols, the font was one of 35 PostScript fonts built into Apple’s Laserwriter Plus, one of the first mass-market laser printers.Credited as helping to kick off the desktop publishing craze, the addition of Zapf Dingbats to the library of fonts available on the Laserwriter allowed anyone to print out symbols and simple images in their documents as efficiently as any other text, without sending more data to the printer.

But even Zapf was only adapting an even older concept to his new digital age: Ornamental dingbats, which allow typesetters to insert pictosymbols into a page of hot type as easily as any other alphanumeric characters, are as old as mechanical printing itself. From that perspective, Johannes Gutenberg himself can claim to be the father of the emoji.

The truth is: As long as we have used machines to mass-produce text, we’ve searched for ways to insert quirky little symbols just as efficiently. The ornamental ivy leaf of a 17th-century dingbat solves the same problems as the smiley face wriggling in your text message today. Like many things, emoji wasn’t invented just once; they were reimagined over and over and over again by countless designers iterating on the same idea: How to insert a little diversity humor, and shorthand into a wall of text appropriately without changing the rules of type.

So don’t mistake emoji for a fad. As long as we have fonts, we’ll have emoji. Even if designers as credible as Zapf, Bigelow, and Holmes have all had their influence on the poo emoji in your text messages, the only true inventor of emoji is typography itself.